Back to Insight Hub

Book Feature: Thomas Sullivan's "Free Speech: From Core Values to Current Debates"

April 19, 2022

by Molly Walsh

|

8 minutes to read

From time-to-time, the Insight Hub will bring you a book feature focusing on authors with Vermont connections.

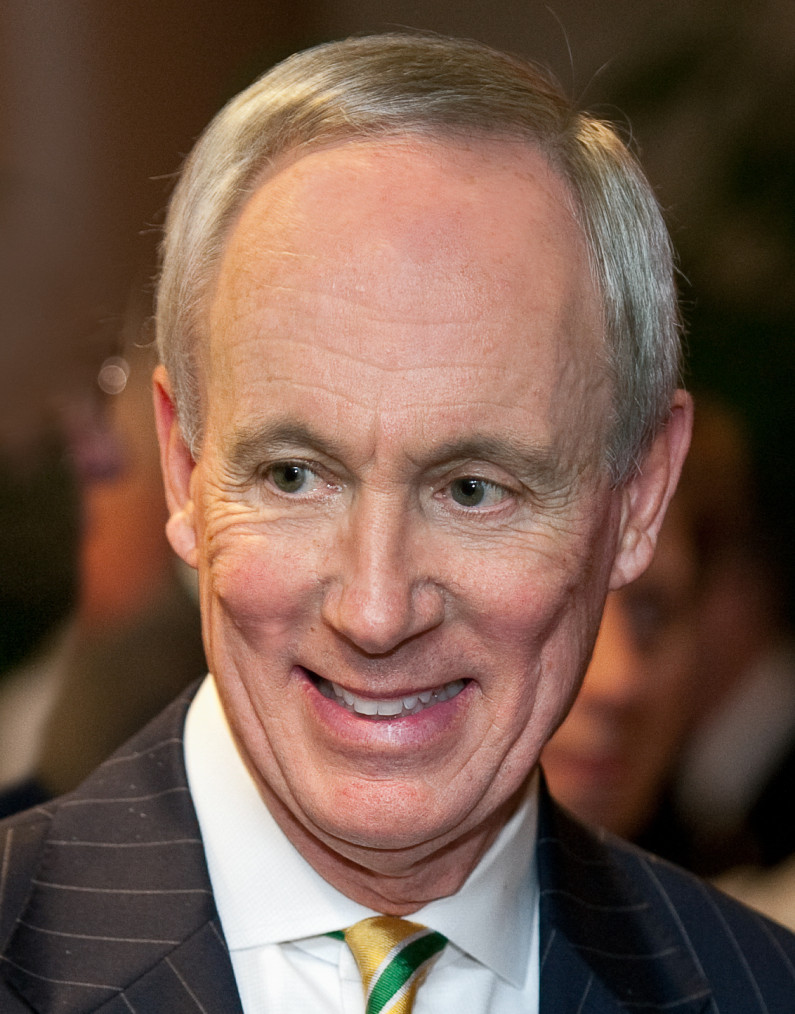

To kick it off, we spoke with University of Vermont (UVM) President Emeritus Thomas Sullivan about teaching, free speech on campus, and his new book on the First Amendment titled, Free Speech: From Core Values to Current Debates, Cambridge University Press, $29.95.

Thomas Sullivan is back at the University of Vermont, but not in the president’s office. These days, the lawyer, antitrust expert, and tenured political science professor who served as president of Vermont’s state university from 2012 to 2019 can be found teaching undergraduates on the Burlington campus. His subject: Free speech—a topic that we have highlighted recently on the Insight Hub as foundational to community connection and resilience (see More Bylines, More Democracy? Attending the Center for Research on Vermont’s 2022 Journalism Conference and Leadership Material: Three ways philanthropy can help expand the leadership pool in Vermont). The following book feature dives into Sullivan’s perspective.

On an early spring afternoon, as gray skies loomed beyond the large windows of his fifth-floor office in the Old Mill Building, Sullivan talked about the importance of the First Amendment and the new book he’s co-authored, Free Speech: From Core Values to Current Debates.

It will be published this month. Meanwhile, Sullivan is using an early edition of the book in his classroom, located across the university green from the marble-columned Waterman building where as UVM president he navigated numerous free speech controversies in real-time.

That work, and Sullivan’s work at institutions of higher learning before he came to UVM, “absolutely” contributed to his decision to write the book, he said.

“Yes, clearly my experience shaped my interest and why I came to the decision to write on this,” Sullivan said. While he avoided dissecting specific UVM controversies in the book, or in this interview, he acknowledged that they could be raw and difficult. His goal was to listen and create dialogue—two concepts he hopes the new book will help promote.

“I would always say to myself, while there may be tension and stress around this, this is a teaching and learning opportunity,” Sullivan recalled.

The book, co-written with University of Michigan law professor Len Niehoff, is crisp and clear, scholarly without being ponderous.

The aim was to write an accessible, one-volume book examining the history of the First Amendment and key U.S. Supreme Court decisions related to it, both from the past and present, including opinions on contemporary issues such as campaign finance, internet speech, and hate speech.

With this knowledge, the authors contend, readers should have better tools to navigate the many thorny questions of free speech weighing upon society today and do so with less division. The book’s larger lesson is that free speech is essential to democracy.

“Without free speech, you cannot have a democracy. It’s a precondition. It’s a precondition so that we can have free and open discussions that inform decision-making as opposed to the tyranny of autocratic, dictatorial, totalitarian regimes that only have one viewpoint and often that’s very narrow and dangerous. Nobody should have a monopoly on ideas,” Sullivan said.

The Now

The current geopolitical situation illustrates the point, with Ukraine supporting free speech and Russia shutting it down, Sullivan added. On the one hand there’s “Ukraine, a democracy, fighting, with the most robust, open society right now, trying to educate people.” On the other, there’s “Russia locking everything down, denying information, (producing) disinformation,” Sullivan said.

Noble it may be, but free speech is messy. The book’s introduction points to the ubiquity of free speech tussles playing out in the workplace, schools, sports venues, college campuses, and popular media.

Should a professional athlete have the right to protest during the national anthem? Can government restrict speech of people with extremist views? Does the media deserve First Amendment protections for spreading “fake news,” and if not, who gets to define “fake news”? Is political correctness resulting in objectionable “self-censorship” and “cancel culture"?

These questions can be even more difficult to answer in an era of political polarization, Sullivan said.

“I’m afraid that a lot of our opinions today are rather knee-jerk one way or the other without a serious reflection on history and facts,” Sullivan said.

Wrangles over free speech often result in stalemate, with each side hunkering down in its corner, the book suggests. In one corner, “absolutists” oppose any speech restrictions, even when speech is damaging, false, or insulting. In the other, “relativists” argue for limitations that in theory might sound reasonable but in practice would gut the concept of free speech. On this score, the book quotes the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter’s admonition against free speech limitations that “burn the house to roast the pig.”

Sullivan hopes the book builds knowledge and gives readers better tools for constructive dialogue. “This is a book that tries to educate first and then invite the great debates,” Sullivan said.

Challenges on College Campuses

No invitation is needed to trigger hot debate on social media, newspaper comment sections, and Reddit chatboards about various free speech issues now filling the headlines, with colleges contributing an outsize number.

Recent tempests include upheaval over the behavior of student protesters at a Yale Law School free-speech panel earlier this year, and controversy about whether former Vice President Mike Pence should be allowed to deliver a speech on “How to Save America from the Woke Left” at the University of Virginia. Pence did make the speech and while protesters waved signs outside the hall, they did not attempt to prevent him from talking inside.

One chapter of Sullivan’s book runs down a long list of campus controversies (mostly without saying where) and discusses how they were resolved, for better or worse.

“Many of these universities were run by friends of mine, or acquaintances of mine,’’ Sullivan said, acknowledging that while he was president of UVM, he read widely about what was going at other universities and sometimes asked himself, “Why did that blow up like that?”

Sullivan, without wanting to single anyone out, said some situations are resolved in a way that does not fully consider free speech rights.

“I also empathize and understand why some leaders may make decision ‘X,’ which is contrary to the First Amendment. Sometimes there are such local political pressures that you have to just kind of swallow hard or it’s going to go badly in another direction for political reasons,” Sullivan said.

Back in the Classroom

Debates in his own classroom have been thoughtful and respectful, Sullivan said, perhaps to the surprise of observers on campus.

Sullivan recounted that one of his faculty colleagues asked him at the beginning of the year whether he was worried that the subject matter of his course might get students “riled up.” Sullivan’s answer? “I said, well, that’s the very purpose of the book, of course, so that we can bring an educational opportunity.”

So far Sullivan has found that teaching First Amendment history and caselaw and then moving to discussion sets the stage for respectful exchanges. “Because of that we’ve had very, I think, sophisticated, deep, civil conversations.”

The bookshelves in Sullivan’s office are full of titles on law and history, including recently published volumes and those collected earlier in his career, which included stretches as provost at the University of Minnesota, dean of the University of Arizona College of Law, and Associate Dean of the Washington University School of Law.

Sullivan wrote or co-wrote a dozen books and many articles on legal issues as he ascended the leadership ranks in higher education. He also made time for the fundraising that is often part of top university jobs.

As president of UVM, Sullivan helped raise more than $600 million and says he never found it a chore. He’s raising money again in the nonprofit world, as board president of the American Bar Foundation in Chicago. It supports inquiry into a range of legal issues, from tenant screening in the U.S. to democracy in China to the role of doctors, family members, and other surrogates in end-of-life decisions.

“All of our money goes to supporting world class scholars doing empirical law and social policy work,” Sullivan said. “That is to say, you’ve got a theory about something, you’ve got an idea about something, go out and find the facts, the evidence. Real, empirical, data to support a proposition or not.”

On Philanthropy

As far as his own giving, Sullivan and his wife Leslie support arts and cultural organizations, along with education, including scholarships for women who are non-traditional-age college students. Another priority is cancer research and research into women’s health. Sullivan’s first wife died of ovarian cancer, and he counts some 10 family members total who have passed away from cancer.

Talking to Sullivan about philanthropy, he ruminated for a moment on how for him it has helped bring into focus the importance of arts and education to nourish the soul—and how health includes wellness strategies to live in the moment, to smile, to laugh, and at the end of the day, think about what’s truly important. His conclusion?

“It’s not that thing that was nagging at me five minutes ago in the office.”

Stay up to date with the latest from the Insight Hub.

Sign up now